- The Frontline Progressive

- Posts

- Madison's Blind Spot

Madison's Blind Spot

What the Founders Didn’t See Coming, and What We Must Do About It

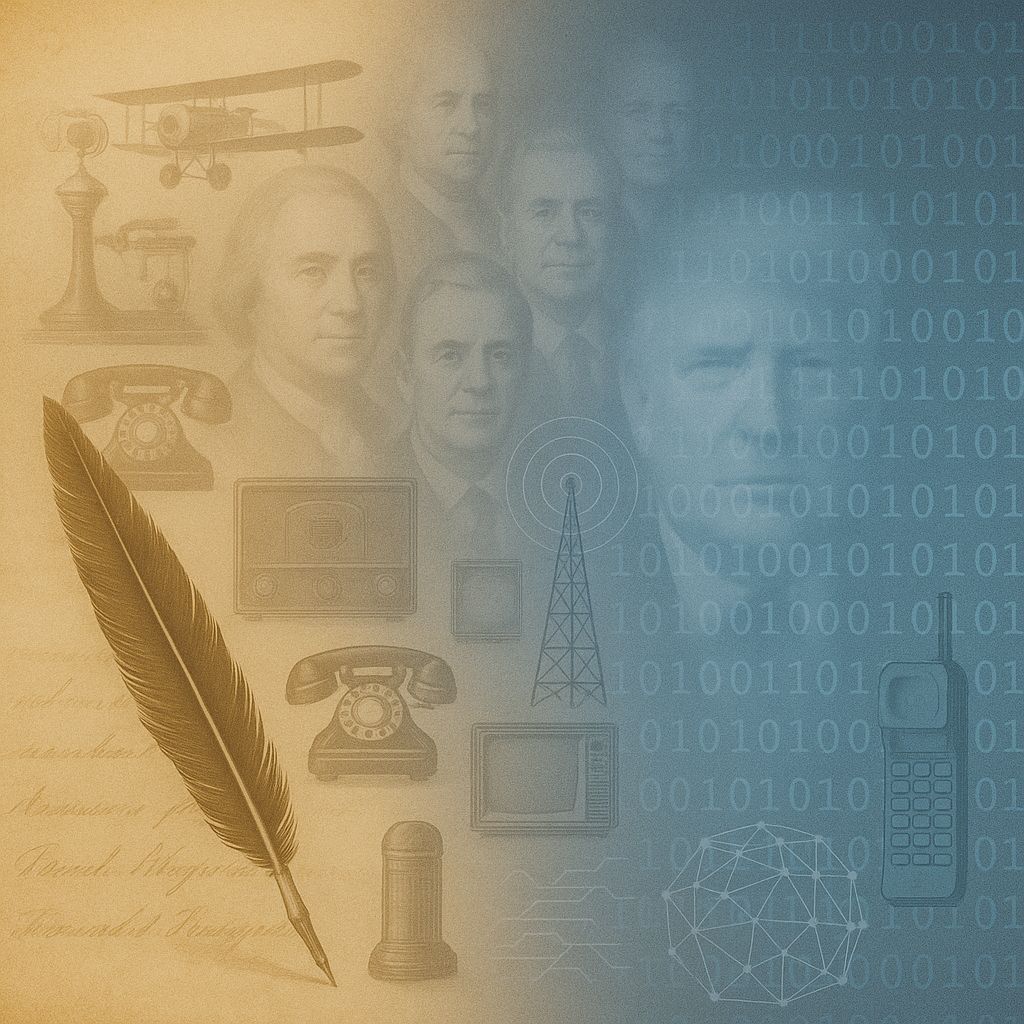

In Federalist No. 10, James Madison wrestled with a timeless question: how can a government remain stable when small groups of citizens, radicalized by grievance, threaten to seize control and tear the nation apart? It’s a question worth asking again today, as a radicalized minority exerts destructive influence over our government and society. Interestingly, the forces that drive radicalization haven’t changed much since Madison’s day. Wealth inequality, unequal property ownership, and gaps in education were concerns then, as they are now.

Madison feared that these divisions could lead to what he called "factionalism," where a group, acting in its narrow interests, undermines the common good. He identified two primary defenses against this threat.

First, Madison advocated for a republic instead of a pure democracy. He distrusted a system in which decisions are made directly by the people because an impassioned majority might devolve into a mob and trample minority rights. A republic, on the other hand, is a representative form of democracy where citizens elect representatives who deliberate and govern on their behalf. Madison believed that these representatives would be insulated from the immediate passions of the crowd, thus acting with greater wisdom and restraint. Furthermore, because a republic draws representatives from across a wide geographic area, Madison reasoned that competing regional interests would minimize local impulses.

Second, he relied on the relatively inefficient flow of information to mitigate coordinated extremism. In the 18th century, news traveled by horseback, and people were relatively isolated from one another. What occurred in Massachusetts might take weeks to reach Georgia, where it would bear little relevance to local affairs. Local factions, separated by distance and time, thus had a limited ability to communicate ideas and unite in a common cause.

But even in Madison’s time, that assumption was already showing cracks. The printing press, for example, challenged his idea of inefficient information spread. Consider the French Revolution, which occurred during Madison’s era. The revolution erupted partly due to the sensationalism circulated through pamphlets and newspapers, proving to be a highly efficient means of uniting people around a common cause. One infamous example was the quote “Let them eat cake.” Even though it was falsely attributed to Marie Antoinette, it infuriated the average French citizen. During America’s founding, figures like Samuel Adams also inflamed revolutionary emotion with his fiery rhetoric in print.

Today, the issue is far more urgent. Modern technology has collapsed the information landscape, shrinking the world to the size of a computer mouse. People are constantly bombarded with emotionally charged content through their mobile phones and computer screens. Selection algorithms are optimized to feed people an information diet that reinforces their biases and triggers their passion. Making matters worse, the elimination of the Fairness Doctrine in the 1980s removed balanced viewpoints in broadcast news and opened the door to hyper-partisan media. At the same time, corporate consolidation of news outlets motivated them to blur the line between journalism and entertainment. Misinformation has become an industry.

Madison’s other bulwark against radicalism has also collapsed. He hoped that political representatives would help mitigate factionalism. But alas, the media has consumed politicians as well, enslaving them to clicks, ratings, and donor dollars. Those who resist the game risk losing their seats to louder, angrier challengers in closed party primaries. The result? Our culture is increasingly shaped by sensationalism and outrage, generating exactly the kind of factional uprising Madison feared.

Madison’s arguments rested on inefficient, diversified communication and reasoned debate among representatives. The digital age destroyed both. His warning in Federalist 10 was well-founded, but his solutions—noble as they were—are no longer enough.

So, what do we do?

A knee-jerk reaction to solving this issue might be to call for the restoration of the Fairness Doctrine, the breakup of media monopolies, and restrictions on algorithm-driven echo chambers. While these proposals could certainly help, they depend on lawmakers and tech companies acting against their own interests. Realistically, that’s unlikely to happen anytime soon. Politicians and technology companies benefit from the current scenario, so they are unlikely to give it up.

Alternatively, a grassroots approach may be a more realistic path forward. It begins with citizen-driven organizations and a renewed commitment to civic-minded reform. One step is to promote and fund public-interest journalism like ProPublica and NPR. Also, newsletters, podcasts, and a growing number of local, nonprofit newsrooms prioritizing accuracy over outrage can help inform people in a non-biased way. These outlets are gaining traction, especially in communities tired of partisan spin.

Another strategy is to use the initiative petition process to implement structural reforms such as open primaries and ranked-choice voting, which reward moderation and reduce extremism. On the educational front, local school boards must invest in stronger curricula for history, social studies, science, and critical thinking. In an era of information overload, young people must be equipped with the intellectual tools to navigate chaos, not fall prey to it.

Additionally, campaign finance reform is a realistic goal at the state and local levels. Increasing transparency about who funds political campaigns, and for what reasons, can help the public identify and resist the influence of hidden or self-serving interests. In addition, communities can invest in programs that promote civil discourse, enabling adults to recognize logical fallacies and rhetorical manipulation.

Ultimately, a well-informed public remains one of the strongest safeguards against the rise of dangerous factionalism.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the reason for the radicalization of our society must be addressed. The wealth gap has left many people with nothing to lose. When you're living paycheck to paycheck, you lose your incentive to maintain the status quo. Instead, you cling to romantic ideas of "burning it all down" because, in a world that takes everything from you and gives nothing in return, it can't get much worse than it is, right? Collectively, we must find ways to give everyone a stake in the success of our nation, not just a privileged few. This topic is the subject of another essay, but suffice it to say that there are some good ideas for improving our society and giving everyone a reason to support it, rather than leaving it to them to find reasons to tear it all down.

Ultimately, Madison’s core ideas remain valid, but they must be modernized and reinforced to give Americans a renewed stake in our shared future.

Reply